Recently I had the great pleasure of making a small contribution to Border Bumping – “a work of dislocative media that situates cellular telecommunications infrastructure as a disruptive force, challenging the integrity of national borders”, by Julian Oliver.

I first met Julian in Linz last year at Ars Electronica where he and Danja Vasiliev were picking up the Golden Nica for Newstweek, and after talking to him for 5 minutes I had the sensation I was talking to somebody from a William Gibson book.

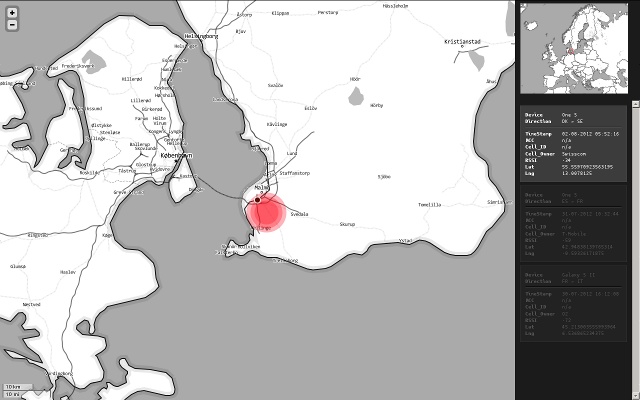

Julian explains the project in the following way on the Border Bumping site: “As we traverse borders our cellular devices hop from network to network across neighbouring territories, often before or after we ourselves have arrived. These moments, of our device operating in one territory whilst our body continues in another, can be seen to produce a new and contradictory terrain for action.. Running a freely available, custom-built smartphone application, Border Bumping agents collect cell tower and location data as they traverse national borders in trains, cars, buses, boats or on foot. Moments of discrepancy at the edges are logged and uploaded to the central Border Bumping server, at the point of crossing. For instance: a user is in Germany but her device reports she is in France. The Border Bumping server will take this report literally and the French border is redrawn accordingly. The ongoing collection and rendering of these disparities results in an ever evolving record of infrastructurally antagonised territory, a tele-cartography.”

As I spent most of last summer bumping into borders, travelling on the TransEuropeExpress, I had already become aware of this situation, especially crossing and re-crossing the Benelux countries. It also brought to mind the fascinating essay by Eleanor Saitta, Transnationality and Performance which begins:

Last week I crossed an international border to install an application on my cellphone. That wasn’t the nominal purpose of the trip, but if we step back from our understanding of internationalization and international copyright law, that interaction between border crossing and the performance of an effectively physical act is almost surreal. More surreal is the possibility (I can’t now check) that I could have simply traded my Icelandic SIM card for my American one and have effectively, virtually, performed that border crossing. That particular pseudo-border is one I’ve been crossing regularly this month. My phone can speak GSM over Wi-Fi, instead of the cellular radio — a feature intended by T-Mobile (the US representatives of a German semi-state entity) to cheaply solve the problem of inadequate coverage at the rural borders of their network and in pockets of urban radio-invisibility. In my case, though, it means that I can trivially make my phone believe temporarily that it’s on American soil, and have calls billed appropriately. Of course, I could actually be on US soil here — the American embassy, whose grounds are legally recognized as such, is just down the road — but my phone wouldn’t notice the difference. Likewise, somehow Roger’s cell towers near the US-Canada border are much stronger than the AT&T or T-Mobile towers; my phone always crosses the border long before I do.

For Border Bumping, Julian asked me to do some research into cell towers, especially so-called “stealth” towers and build an archive mapping them. Sounds simple, huh? But just as we found when we tried to map Internet connectivity for the ChokePoint Project, reliable publicly available information on the geolocacalisation of cell towers is actually pretty hard to find. The situation isn’t helped by the fact that mobile service providers aren’t obliged to provide information as is shown in this statement from the Sitefinder – Mobile Phone Base Station Database website of Ofcom, the Independent regulator and competition authority for the UK communications industries:

Consequently finding information to build the database involved a lot of sniffing around online. Fortunately there are cell-tower nerds out there who go out and map this stuff but there is no coherent set of criteria that everyone uses.

The initial Border Bumping archive can be found here